Binding: Tradepaper

Size: 6 x9; Pages: 68

Price: US $16.00

Pub Date: March 1st, 2018

$16.00Add to cart

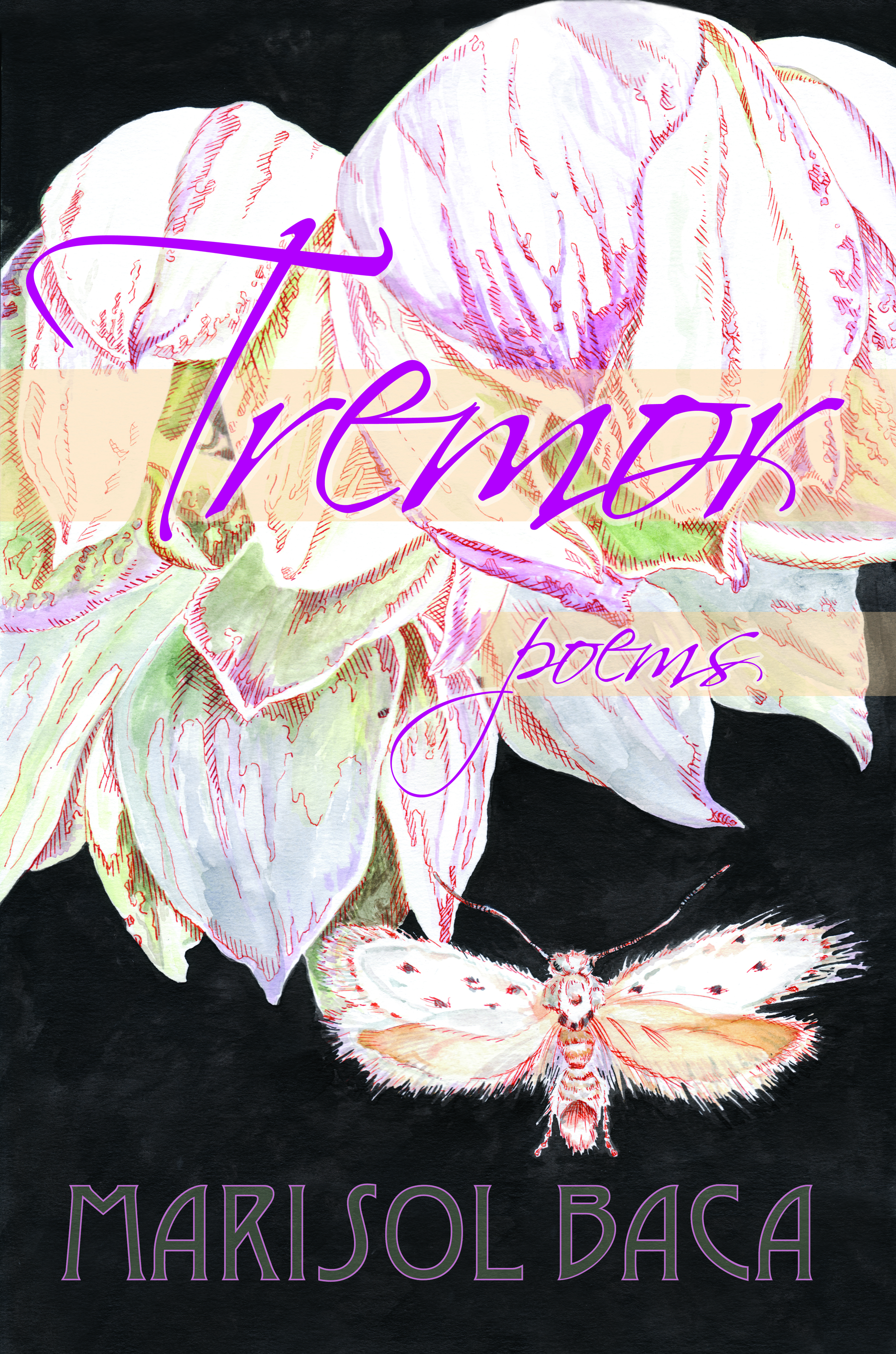

Marisol Baca’s debut collection Tremor is a journey through shimmering landscapes and innerscapes. Interlacing the past and the present through the lens of her Mexican-American heritage, Baca unspools profound connections – life and death, her grandmother’s legacy and earth’s graces – in poems that move the reader with quiet strength and beauty. Both narrative and lyrical, Baca’s poems are like small earthquakes that shake you subtly but undeniably; life is changed after reading her.

Praise for Tremor:

“Marisol Baca, the dream painter, the undulating desert and shaking ocean caller whose poems here take you under where death delights in New Mexico ovens, “green tongues,” “the whole town crying,” and most of all, the “tentacular lust” of things that no one sees. These poems unwind and disrupt our perceptions of the real and operate in the material of mist, fog, “shingles and rats,” the “teal inkiness” in this “bowl of space” we inhabit. I am caught in her Chagall palette, in her Remedios Varo floating realms, in her fearlessness of decomposition, reconnection — and most of all these investigations into nothingness, the “inner lining,” the movement of upside-down membranes and “stray universes.” We must notice this in our tiny life before it explodes with “one hundred thousand / sterile sisters” crawling up our legs. A serrated soul-piercing Geiger Counter. Shattering. Prize. Absolutely love this collection.–Juan Felipe Herrera, Poet Laureate of the United States 2015-2017

Tremor is a kiln, a flood, a dirge, and a dream. Herein, you will enter a world of demolition and transformation, a world of resilient women and spirits, a world made of hearts and heart eaters, a universe where meaning wildly detonates and sprouts: “One hundred years the grandparents stayed together./ One hundred years on an avocado sofa./ Transfixed on making meaning.” In this startling collection of lush landscapes of alfalfa & braids & horses & teeth, Marisol Baca is an archaeologist of the vivid and the revenant, tracing the magnitude of inheritance and the intense irrevocability—sometimes beautiful, sometimes agonizing—of having a body. What happens when you notice the unwieldy cosmos—its births & deaths—in your house? In the bodies you love? This. This Tremor—everything knotted with memory and destiny; fecundity and loss both coiled in the kitchen, “the green tongues” of chile “speechless in their hands;” every life a cosmos, and “What is the cosmos but a radial movement outward?” Through extraordinary scenes, pulsating language, and an otherworldly emotional X-ray vision, Baca reminds us there is no living form that is not an epilogue for the vanished—“the ocean was nowhere,/ except in the recesses of their minds”—and no evacuated form that cannot be restocked with the living—“nebula […] mixed up in his hair,” “her voice filled with weeds,” “the sound of bees in her ears.” Baca’s voice is like nothing I’ve heard before, is made of the same fire and water that first sparked life into clay. Prepare yourself. These poems are ravishing in their knowing, and ravening in their truths, and “we do not know when the ants/ will come and devour everything.” —dawn lonsinger, author of Whelm, 2013

“There is no fence, or rather, there is this fence: a cloud of / linen napkins to separate the earth from sky,” Marisol Baca writes, and these poems line up one square after another as a book into its own “white, cotton banner,” flagging the division between what is earth, and what is lonely sky. For the poet, what is earth is literal and enmeshed with the body: clay and straw stalks dome into the family horno, chiles welt hands, a pebble lodges the throat, and moving from their desert Southwest, the book’s speaker and her father must walk the ragged edges of land mounded by sailor jellyfish blown ashore. But what is sky is much more difficult, and the book traces from family stories portraits of grandparents and a father “obscured by fog” and “in a world of margins.” The father who fills his pockets with jellyfish in order to throw them back into the ocean in one poem is the same man who, in another poem is dying, his multiple sclerosis a “spasticity / of lies . . . communicating a crustaceous desire,” and grief functions as lasso in these poems, the poet attempting to close in from the air and smoky memory some incalculable cipher. Baca asks “[w]hat is the word for that squeak before a moan?” and these poems linger in clouds as much as alfalfa fields in such unanswered suspension. —Sasha Pimentel, author of For Want of Water: And Other Poems, 2017; and Insides She Swallowed, 2010.

DYAD

She wishes she had the ability to become larger.

The monolith is pointing her toward herself.

She hates that direction, better to wash a hand, walk

backward, turn away from yourself, eat the fragments.

Swallow a river of arrows pointed at each other.

This makes you bigger.

Too big you can’t fit in your life.

Swallow a banner fluttering, pointed at home.

Small. She is fish eye, turtle egg.

The first map she makes is on the skin of a cloudy

mushroom. On it is written a correspondence:

the two selves looking on opposite sides

of a dividing line. Where my hand points, the other

is reflected. She is four now, she is an infinite tiny self.

–from Tremor